Remembering the dead in rural Catalunya

international |

environment |

feature

international |

environment |

feature  Tuesday November 03, 2009 14:12

Tuesday November 03, 2009 14:12 by 1 of imc

by 1 of imc

Commemorating the Battle of the Ebro in the Terra Alta

Seventy years after the Battle of the Ebro the dead remain unburied and the ghosts of Franco's dictatorship still haunt the landscape. Indymedia investigates...

Related Links:

A Catalan blogger's post on the remains in the Terra Alta | An English translation of Elies 115's original post | Website for the old town of Corbera | The official state-sponsored website for the Battle of the Ebro

Human bones at the edge of a forest outside la Fatarella |

There’s

something of a feel of the backwoods in the northern hills of

the Terra Alta, that part of Catalunya tucked into the mountains west

of the Ebro. Here, the high ground to the north of the main valley is

scored with crooked lines of olive and almond trees, stone-terraced

into the hillsides between patches of parched scrubland and isolated

wooded summits. An occasional ruin breaks the skyline or nudges into

the side of a barranca but by Irish standards,

the landscape is

depopulated and abandoned. The area is of course extraordinarily

beautiful, as we'd say in Ireland, unspoilt. Most people from around here live in the small towns of la Fatarella, Vilalba dels Arcs or further west in Batea. Isolated farmhouses do hang on in decreasing numbers, some offering rough wine-tasting during the day, others a rustic bed and breakfast to souls needful of a particular quality of isolation. For here ruins remain ruins. There are no dilapidated fincas receiving the attentions of well-intentioned ex-pats, there are few enough Es Ven signs fixed to broken walls. Here the crumpled sun-dried placards advertising properties marketable in an earlier economy lie forgotten alongside the road, littered among rusting sherds of shrapnel and fragments of human bone. The valley below carries the main road from Tarragonna west into Aragón. The ruined hilltop village of Corbera d’Ebre, its church spire proud and intact, dominates the eastern end of the valley and overshadows the new town straddling the road. Corbera was heavily bombed by the Nationalists over the course of the great Ebro offensive launched by the Republic in July 1938 and like Belchite to the west, it has been left to the elements and to the tourists, discomforting reminders of an unresolved conflict, the memory of which so-far has been successfully managed by the Catalan state. |

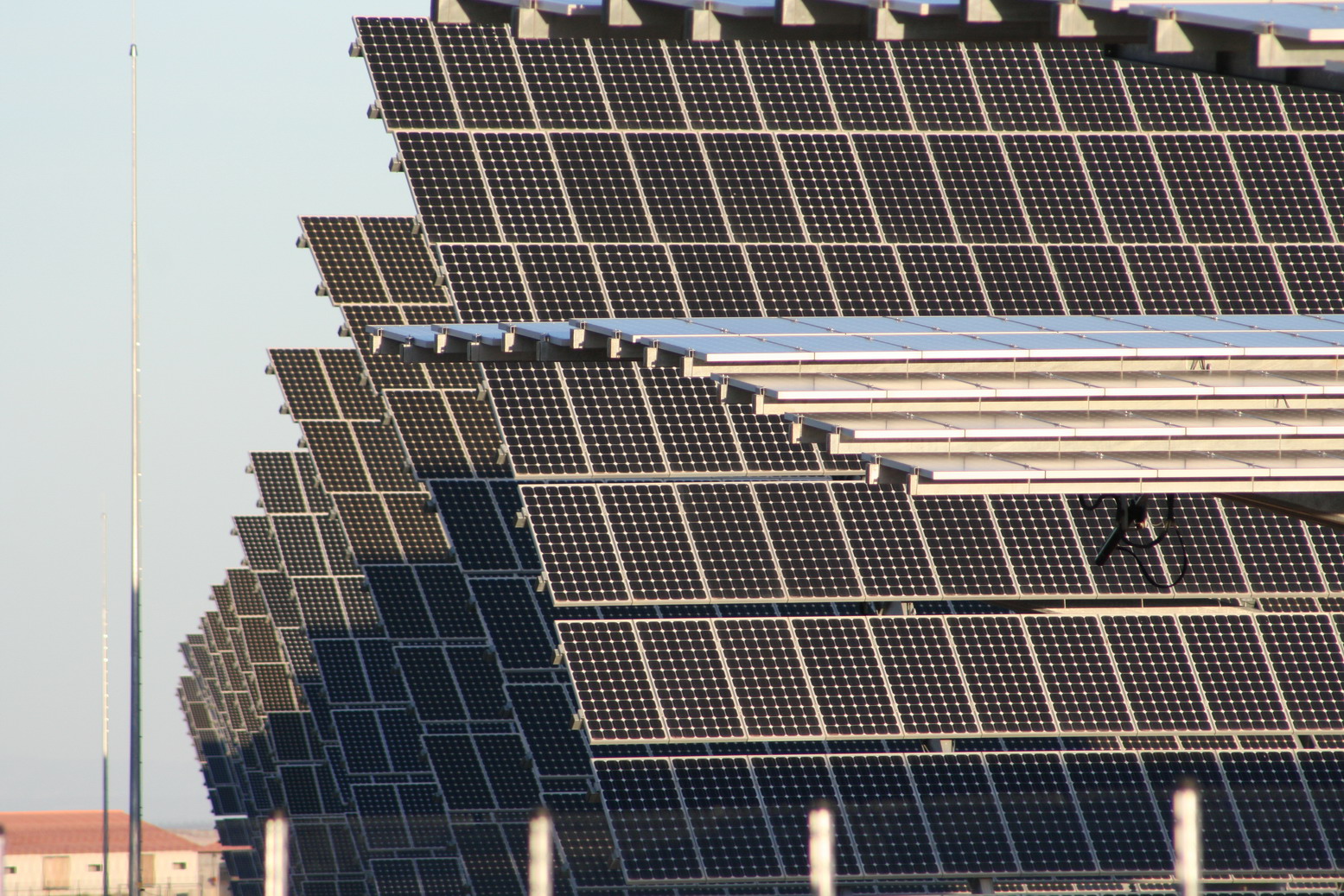

| The main road

continues west to the town of Gandesa, the military focus

of the battle, which though lasting just 115 days took over 130,000

lives. South of here are the Serra Cavalls which rise up into the

serrated peaks of the Serra de Pàndols, their heights delineated by the

pine tree line which occasionally obscures the ridge. Go further west

through Calaceite and here the high ground recedes at either side.

Beyond Alcañiz and further into Aragón the landscape opens onto a wide

upland plateau ringed by distant mountains, with massive fields of

winter wheat carpeting a rolling steppe extending onwards to a point

just beyond eyeshot. On the road to Belchite an area of several square

kilometres accommodates a sun farm, manifesting on the landscape as an

army of flat-headed alien warriors arranged in tilted ranks, dwarfing a

surprisingly flimsy fence. All of these landscapes are central to the history of the XV International Brigade, from the initial storming of Belchite and Quinto but more crucially to what become known as the Great Retreats of March and April 1938, where Republican forces were progressively routed back towards and across the Ebro. Many Internationals caught behind the lines were summarily executed with others surviving the remainder of the war in concentration camps such as San Pedro de Cardeña outside Burgos. When the Brigade advanced back across the Ebro the following July, local people showed them the mass graves into which their comrades had been thrown, often after the quick executions they themselves had been forced to witness. In any event, the Brigade never succeeded in taking Gandesa and was withdrawn in September after 60 days in the line. The Ebro offensive was the last throw of the dice for the Republican government and its initial success was something of an embarrassment for Franco who was again forced to call upon his German and Italian allies, just at the point where he was about to send them home. The nature of Franco’s defeat of the Republican government and the subsequent repression which lasted well into the 1970s was particularly felt in Catalunya, which apart from its separatist aspirations was the principal industrial base of the CNT, the main anarchist trade union. In the countryside, the repression was initially marked by the liquidation of anyone said to have actively opposed the coup, followed quickly by the banning of the Catalan language and a rationing system which was markedly more severe than in ostensibly ’loyal’ areas. Nationalist battlefield fatalities were recovered and buried in the combatants’ home localities. International causalities, with a few significant exceptions, were buried hurriedly in mass graves or, in more remote areas, piled into the barrancas and pine copses which bestow the hills their remarkable landscape and covered with cairns of stones. |

Sun farm close to a rearguard position outside Belchite |

Monument to the battle incorporating an ossuary at los Camposines |

The roads in

the Terra Alta are dark and untravelled at night time, the

older ones, tarred-over dusty tracks, snake over the hills in tight

curves around stepped orchards and dry stream beds. The main roads into

Gandesa and Ascó are now being straightened to facilitate the

construction of a large wind farm enveloping the hilltops in seemingly

arbitrary patterns covering perhaps some 80km. The 6km between la

Fatarella and Vilalba accommodates some 22 windmills, with bulldozers

clearing stretches of land for associated access roads and ancillary

structures. Driving along at night, their gigantic spines rear up on

all sides, frozen shadows projected in random sequence against the

verges, caught in the pulsing strobes from the derrick lights high

above. Local environmentalists opposed to this section of the wind farm

were not slow to recognise its route across a massive graveyard in

their campaign to halt their development. One such opponent, Elies 115

(whose blog is worryingly subtitled Déu, Pàtria i Honor),

graphically

illustrated the human remains encountered on a walk through the hills

near la Fatarella in July 2008 and the story was picked up all over

Catalunya. Many subsequently voiced an opinion in the local media that

had Roman remains been encountered, all works would have stopped to

allow a thorough investigation. What differentiates the remains recorded by Elies 115 from those emerging from other mass graves in the Spanish countryside is the fact that they most probably belong to members of the International Brigades. Although it is not suggested here that this has precluded a proper investigation of their remains, it is nonetheless of interest given the considerable body of literature associated with the Brigades when compared to their number relative to the republican army as a whole. For archaeological work engaging with Franco-era Spain has concentrated mostly on civilian mass grave sites. These hold the remains of the many thousands of socialists, communists, anarchists, schoolteachers and even liberals, executed for their beliefs, their resistance to the victors or simply by hearsay. Excavations have been undertaken under the auspices of the Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, a body established on a grassroots basis in 2000, which has calculated the existence of some 30,000 such sites throughout the country. In the Priorat region of Catalunya, on the far side of the Ebro from Terra Alta, the organisation No Jubilem La Memòria focuses more on commemoration and education with some significant attention being paid to the role of the International Brigades in the conflict. The excavations throughout Spain have now uncovered hundreds of burials, emphasising the oppression supposedly forgotten under the post-Franco pact of amnesia, where old wounds were let lie for the good of the fledging democracy. Politically, this is to the advantage of the Socialist PSOE and the enacting of the Ley de Memoria Histórica (Law of Historical Memory) in 2007 has undeniably given the excavations a legislative basis, irrespective of feelings on the Nationalist side. Often undertaken in the media spotlight with relatives of the deceased present standing along the baulks, the excavations provide harrowing testimony of the extent of the Nationalist repression. |

Other more contentious issues have emerged: the muted enthusiasm of some families for the closure provided by the recovery of physical remains of their loved ones has contrasted with the discomfiture evident on the faces of the family of Federico García Lorca, who are at this moment awaiting the excavation of his remains after refusing for many years to have his grave disturbed. In Galicia and León former huídos, partisans who remained behind to continue the war from the mountains, have argued that the remains of their comrades should stay in the ground as incontrovertible and enduring evidence against Franco and his regime. An archaeological investigation undertaken prior to the construction of another wind farm elsewhere in the Terra Alta made little of the human bones and battlefield détruis scattered along the terraces and in the scrub. The report made more of the trenches, the rude caves and refugios carved out of the sandy subsoil, lending thirsty shelter from the constant Nationalist bombardment; the physical manifestations of the battle which today survive on the landscape. Yet, despite the plethora of recent work on the period, both academic and commemorative, there has been little attempt made to contextualise the human remains, which as likely date to the Great Retreats as they do to the Ebro offensive. Moreover, there has been little discussion as to what should now be done with the bones, whether they should lie there in perpetual memory of the war or whether they should be systematically collected and placed in the monument at los Camposines which acts as a ossuary for human remains recovered from the surrounding fields and hillsides. State-sponsored commemoration of the battle of the Ebro was prompted by last year’s 70th anniversary and has taken the form of a series of panels located at significant points on the landscape, all anchored to an interpretative centre in Corbera and notionally to the monument in los Camposines. Under the auspices of Memorial Democràtic the Catalan government has certainly made an effort to commemorate both sides of the conflict, the rusty orange signage and an accompanying series of information leaflets brands its commemoration for modern, all-embracing consumption. The souvenirs and tee shirts available at the 115 Days centre in Corbera are based on the graphic of a military helmet, one curiously more Republican than Nationalist in its typology. The interpretation within is dispassionate and uncontroversial; the centre, an anodyne exercise in contemporary architecture, was deserted the afternoon we visited. |

The ruins of the old town of Corbera |

Private museum at Corbera |

Just up the street from the interpretative centre is a private museum, Exposició La Trinxera, which trades in bullets, guns and (mostly) republican uniforms draped over ‘70s shop window mannequins. Here a different experience is to be had: the exhibition confined to one large cluttered room, old-fashioned display cases line the space containing a mesmerising quantity of personal equipment and assorted militaria; the walls are covered with campaign maps, propaganda sheets and government proclamations. The floorspace is taken up with a full sized Republican command post along with various large weapons and a mule professionally fashioned from wire, carrying the obligatory ammunition boxes. The owner/curator has a large shed to the rear crammed with similar booty and takes particular pride that his Maxim machine gun is an original artefact, unlike that one displayed in another semi-private museum down the road in Gandesa. One returns to the sunlight with thirsty lungs, convinced that the patched, ragged costumes within have been taken from the dry bones lying out on the hills. A different engagement with the memory of the battle can be experienced in the ruined village on the hilltop, itself a protected historical site. Here local artist Jesús Pedrola has for several years curated the Alphabet of Freedom, a collaborative project comprising large letters arranged throughout the ruined streetscape by visiting artists in a variety of media and styles. More recently a more formal entity, the Patronage del Poble Vell, has been set up by members of the community backed by the local council with the clear objective of ‘preserving and restoring’ the site. According to their website 'A lot of people visit the site and it concerns our own history. A history testified in the stones which we wish to restore and preserve, to leave in better condition for the younger generation. We don't wish the site to be lost or to deteriorate more.' The inherent technical challenge of trying to preserve a site already in ruins has not however been addressed and it will be interesting to see how in the future Corbera will weigh up against Belchite, a less visited spot yet one which seems to diminish with each passing year. |

| One of the

objectives of the Patronage is to create a

photographic

archive that will serve to preserve the memory of the village as it

was, while at the same time providing an exhibition space for donated

works from artists associated with the alphabet project. A

semi-derelict house on the edge of the old village has been acquired

and is about to undergo conservation works, funded by ANAV, the power

company which operates the 40-year old nuclear plant on the Ebro at

Ascó. The house stands directly beside the building Pedrola has been

reconstructing over several years at his own cost, which functions as

an information point for those visiting the ruined village. He is now

under pressure from the town hall to close up the building, which

provides him with a meagre income to protect the alphabet through the

sale of books and posters. He worries how Corbera’s story will be

presented in the new building and is suspicious of the input from ANAV,

where the power plant is still seen as a legacy of the dictatorship. Those supporting the construction of the wind farms point to the nuclear plant and its abysmal safety record. The most recent incident relates to a serious leak which occurred in November 2007: although radioactive particles were still being detected outdoors on 14 March 2008, the Spanish Nuclear Energy Authority was not informed of the incident until 4 April. Local groups were incensed that staff at the plant had allowed a school trip to go ahead just a day before the leak was made public. In August the Energy Authority announced penalties against the plant of up to €22.5 million for a series of breaches, including their failure to immediately report the leak. The Zapatero government has pledged to make Spain nuclear-free, but has not proposed a meaningful time frame. Meanwhile it’s hoped that the sun and the wind can provide an ever-increasing proportion of the country’s needs into the future. Back up in the hills, the construction of the wind farm continues apace. With most of the windmills already erected, those opposed to their construction are admitting defeat. But what of the human remains that have been disturbed in their construction? On 17 June last the Catalan parliament passed legislation on the recovery and identification of those who disappeared during the Civil War and subsequent dictatorship. The new law places the onus on the Catalan state to locate the graves of missing persons, supporting the rights of their descendants to obtain information about their fate and, if appropriate, to excavate their remains. The law further supports the marking of such mass graves and their preservation as places of memory, to satisfy people’s right to know the truth of events during the period and the political circumstances in which the disappearances occurred. As García Lorca’s descendants are about to discover, the science of DNA matching has advanced sufficiently to allow the identification (or otherwise) of remains from known burial sites. Attempting, however systematically, to recover individual lives and histories from disarticulated bones gathered from the hillsides is another story. Given that the remains are as likely to belong to volunteers from outside Spain renders the task all the more impossible. It perhaps serves a greater purpose that the bones should remain where they lie with their anonymity intact, a reminder for all of the sacrifices made in the attempt to defeat fascism in Spain. In an economy where ruined villages compete with private museums and interpretative centres, where international solidarity has been replaced by the globalised capital of the power companies, perhaps the only real experience left is to walk through the landscape yourself, your back to the windmills and your eyes to the ground against the sun. |

Jesús Pedrola, curator of the Alphabet of Peace |

Those interested in the issues raised here may want to attend a talk by Prof Ermengol Gassiot (University of Barcelona) entitled ‘The Politics of Memory: Unearthing Mass Graves from the Spanish Civil War’. It’s on Friday 13 November in Room C6002 in the Arts Block, TCD between 13.00-14.30.