North Korea Increases Aid to Russia, Mos... Tue Nov 19, 2024 12:29 | Marko Marjanovi? North Korea Increases Aid to Russia, Mos... Tue Nov 19, 2024 12:29 | Marko Marjanovi?

Trump Assembles a War Cabinet Sat Nov 16, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi? Trump Assembles a War Cabinet Sat Nov 16, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi?

Slavgrinder Ramps Up Into Overdrive Tue Nov 12, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi? Slavgrinder Ramps Up Into Overdrive Tue Nov 12, 2024 10:29 | Marko Marjanovi?

?Existential? Culling to Continue on Com... Mon Nov 11, 2024 10:28 | Marko Marjanovi? ?Existential? Culling to Continue on Com... Mon Nov 11, 2024 10:28 | Marko Marjanovi?

US to Deploy Military Contractors to Ukr... Sun Nov 10, 2024 02:37 | Field Empty US to Deploy Military Contractors to Ukr... Sun Nov 10, 2024 02:37 | Field Empty Anti-Empire >>

Indymedia Ireland is a volunteer-run non-commercial open publishing website for local and international news, opinion & analysis, press releases and events. Its main objective is to enable the public to participate in reporting and analysis of the news and other important events and aspects of our daily lives and thereby give a voice to people.

Fraud and mismanagement at University College Cork Thu Aug 28, 2025 18:30 | Calli Morganite Fraud and mismanagement at University College Cork Thu Aug 28, 2025 18:30 | Calli Morganite

UCC has paid huge sums to a criminal professor

This story is not for republication. I bear responsibility for the things I write. I have read the guidelines and understand that I must not write anything untrue, and I won't.

This is a public interest story about a complete failure of governance and management at UCC.

Deliberate Design Flaw In ChatGPT-5 Sun Aug 17, 2025 08:04 | Mind Agent Deliberate Design Flaw In ChatGPT-5 Sun Aug 17, 2025 08:04 | Mind Agent

Socratic Dialog Between ChatGPT-5 and Mind Agent Reveals Fatal and Deliberate 'Design by Construction' Flaw

This design flaw in ChatGPT-5's default epistemic mode subverts what the much touted ChatGPT-5 can do... so long as the flaw is not tickled, any usage should be fine---The epistemological question is: how would anyone in the public, includes you reading this (since no one is all knowing), in an unfamiliar domain know whether or not the flaw has been tickled when seeking information or understanding of a domain without prior knowledge of that domain???!

This analysis is a pretty unique and significant contribution to the space of empirical evaluation of LLMs that exist in AI public world... at least thus far, as far as I am aware! For what it's worth--as if anyone in the ChatGPT universe cares as they pile up on using the "PhD level scholar in your pocket".

According to GPT-5, and according to my tests, this flaw exists in all LLMs... What is revealing is the deduction GPT-5 made: Why ?design choice? starts looking like ?deliberate flaw?.

People are paying $200 a month to not just ChatGPT, but all major LLMs have similar Pro pricing! I bet they, like the normal user of free ChatGPT, stay in LLM's default mode where the flaw manifests itself. As it did in this evaluation.

AI Reach: Gemini Reasoning Question of God Sat Aug 02, 2025 20:00 | Mind Agent AI Reach: Gemini Reasoning Question of God Sat Aug 02, 2025 20:00 | Mind Agent

Evaluating Semantic Reasoning Capability of AI Chatbot on Ontologically Deep Abstract (bias neutral) Thought

I have been evaluating AI Chatbot agents for their epistemic limits over the past two months, and have tested all major AI Agents, ChatGPT, Grok, Claude, Perplexity, and DeepSeek, for their epistemic limits and their negative impact as information gate-keepers.... Today I decided to test for how AI could be the boon for humanity in other positive areas, such as in completely abstract realms, such as metaphysical thought. Meaning, I wanted to test the LLMs for Positives beyond what most researchers benchmark these for, or have expressed in the approx. 2500 Turing tests in Humanity?s Last Exam.. And I chose as my first candidate, Google DeepMind's Gemini as I had not evaluated it before on anything.

Israeli Human Rights Group B'Tselem finally Admits It is Genocide releasing Our Genocide report Fri Aug 01, 2025 23:54 | 1 of indy Israeli Human Rights Group B'Tselem finally Admits It is Genocide releasing Our Genocide report Fri Aug 01, 2025 23:54 | 1 of indy

We have all known it for over 2 years that it is a genocide in Gaza

Israeli human rights group B'Tselem has finally admitted what everyone else outside Israel has known for two years is that the Israeli state is carrying out a genocide in Gaza

Western governments like the USA are complicit in it as they have been supplying the huge bombs and missiles used by Israel and dropped on innocent civilians in Gaza. One phone call from the USA regime could have ended it at any point. However many other countries are complicity with their tacit approval and neighboring Arab countries have been pretty spinless too in their support

With the release of this report titled: Our Genocide -there is a good chance this will make it okay for more people within Israel itself to speak out and do something about it despite the fact that many there are actually in support of the Gaza

China?s CITY WIDE CASH SEIZURES Begin ? ATMs Frozen, Digital Yuan FORCED Overnight Wed Jul 30, 2025 21:40 | 1 of indy China?s CITY WIDE CASH SEIZURES Begin ? ATMs Frozen, Digital Yuan FORCED Overnight Wed Jul 30, 2025 21:40 | 1 of indy

This story is unverified but it is very instructive of what will happen when cash is removed

THIS STORY IS UNVERIFIED BUT PLEASE WATCH THE VIDEO OR READ THE TRANSCRIPT AS IT GIVES AN VERY GOOD IDEA OF WHAT A CASHLESS SOCIETY WILL LOOK LIKE. And it ain't pretty

A single video report has come out of China claiming China's biggest cities are now cashless, not by choice, but by force. The report goes on to claim ATMs have gone dark, vaults are being emptied. And overnight (July 20 into 21), the digital yuan is the only currency allowed. The Saker >>

Brace Yourselves Once Again for the Mask Madness Tue Dec 16, 2025 13:29 | Dr Gary Sidley Brace Yourselves Once Again for the Mask Madness Tue Dec 16, 2025 13:29 | Dr Gary Sidley

The mask mafia is back. The UK faces "a tidal wave" of 'super flu' and people must "get back into the habit" of mask-wearing, says one senior NHS mandarin. We have one defence, says Dr Gary Sidley: do not comply.

The post Brace Yourselves Once Again for the Mask Madness appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

?Depopulation, Vaccination and Movement Restrictions?: ?Cow Covid? Measures Spark Revolt in France Tue Dec 16, 2025 11:13 | Will Jones ?Depopulation, Vaccination and Movement Restrictions?: ?Cow Covid? Measures Spark Revolt in France Tue Dec 16, 2025 11:13 | Will Jones

The slaughter of entire herds of cattle to combat a disease outbreak in France has sparked widespread protests and a farmers' revolt amid comparisons to draconian Covid measures.

The post “Depopulation, Vaccination and Movement Restrictions”: ‘Cow Covid’ Measures Spark Revolt in France appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

Heroic Muslims Are Not the ?Antidote? to Islamist Terror Tue Dec 16, 2025 09:15 | Steven Tucker Heroic Muslims Are Not the ?Antidote? to Islamist Terror Tue Dec 16, 2025 09:15 | Steven Tucker

After the awful massacre of Jews on Bondi beach, far too many commentators focused on the actions of the heroic Muslim who tackled one gunman. Heroic Muslims are not the "antidote" to Islamist terror, says Steven Tucker.

The post Heroic Muslims Are Not the ?Antidote? to Islamist Terror appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

The EU?s Climate Targets Will Not Last Long Now Tue Dec 16, 2025 07:00 | Ben Pile The EU?s Climate Targets Will Not Last Long Now Tue Dec 16, 2025 07:00 | Ben Pile

The EU's rollback of its petrol and diesel car ban is just the start of the bloc's retreat from Net Zero, says Ben Pile. Emissions reduction targets may remain in place for now, but don't imagine they will last long.

The post The EU’s Climate Targets Will Not Last Long Now appeared first on The Daily Sceptic.

News Round-Up Tue Dec 16, 2025 01:09 | Will Jones News Round-Up Tue Dec 16, 2025 01:09 | Will Jones

A summary of the most interesting stories in the past 24 hours that challenge the prevailing orthodoxy about the ?climate emergency?, public health ?crises? and the supposed moral defects of Western civilisation.

The post News Round-Up appeared first on The Daily Sceptic. Lockdown Skeptics >>

Voltaire, international edition

Will intergovernmental institutions withstand the end of the "American Empire"?,... Sat Apr 05, 2025 07:15 | en Will intergovernmental institutions withstand the end of the "American Empire"?,... Sat Apr 05, 2025 07:15 | en

Voltaire, International Newsletter N?127 Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:38 | en Voltaire, International Newsletter N?127 Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:38 | en

Disintegration of Western democracy begins in France Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:00 | en Disintegration of Western democracy begins in France Sat Apr 05, 2025 06:00 | en

Voltaire, International Newsletter N?126 Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:39 | en Voltaire, International Newsletter N?126 Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:39 | en

The International Conference on Combating Anti-Semitism by Amichai Chikli and Na... Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:31 | en The International Conference on Combating Anti-Semitism by Amichai Chikli and Na... Fri Mar 28, 2025 11:31 | en Voltaire Network >>

|

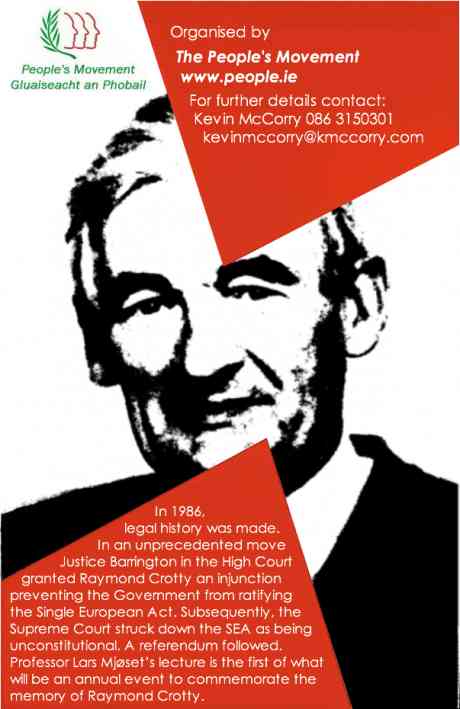

When Histories Collide: Raymond Crotty's intellectual significance

national |

anti-capitalism |

press release national |

anti-capitalism |

press release

Wednesday October 13, 2010 22:48 Wednesday October 13, 2010 22:48 by O. O'C. - People's Movement by O. O'C. - People's Movement kevinmccorry at kmccorry dot com kevinmccorry at kmccorry dot com 086 3150301 086 3150301

It is not without significance that this book was never reviewed in Ireland.

Raymond Crotty's intellectual significance was recognised outside of Ireland as is evidenced by extracts from reviews of his last book, When Histories Collide, 2001, by Professor Charles Tilly, historian and sociologist, University of Columbia, New York:

"Raymond Crotty has the knack of seeing form the ground up processes that others have viewed from the top down. He had the agronomic and comparative experience to recognize what he was seeing. The result is a fresh, challenging, at times astonishing set of insights into relations between agriculture and civilization."

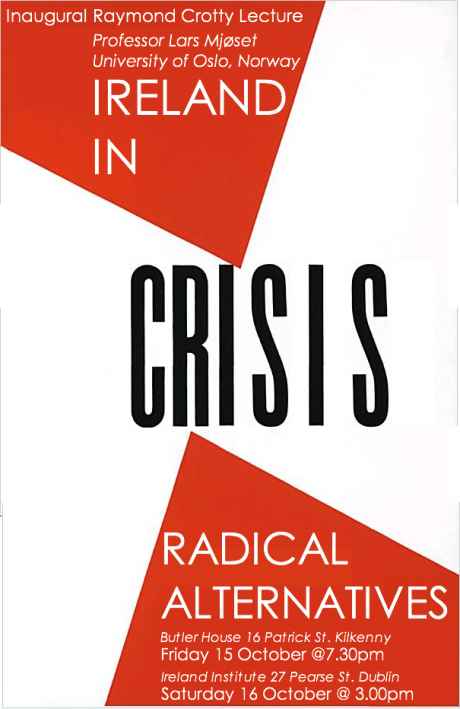

'Ireland in Crisis, Radical Alternatives', Lecture by Professor Lars Mjøset, University of Oslo, Norway in memory of Raymond Crotty. Butler House, 16 Patrick Street, Kilkenny, 15th October, 7.30 p.m. and Ireland Institute, 27 Pearse Street, Dublin, 16th October at 3.00 p.m.

Both lectures are organised by the People's Movement.

Inaugural Raymond Crotty Lecture: Ireland in Crisis, Radical Alternatives (Kilkenny, 15th October; Dublin 16 October) Review of When Histories Collide, by Professor Michael Mann, University of California, Los Angeles, in Contemporary Sociology

Raymond D. Crotty. When Histories Collide. The Development and Impact of Individualistic Capitalism. Walnut Creek, California: Rowan & Littlefield, 2001, 311pp. http://tinyurl.com/34y6c96

This is an extraordinary book by an extraordinary man. For fifteen years a farmer in County Kilkenny, Ireland, Crotty began to write a column for the Irish Farmers Journal. He took an undergraduate degree by correspondence course and followed this with a master's degree at London University. He sold his farm, became an agricultural economist and worked as a consultant with international aid agencies. He authored books on the Irish economy and politics and on cattle farming. He had largely finished the manuscript of this much more ambitious book in 1992, but he died in 1994 before it was ready for publication. His son struggled through rejections of the manuscript but eventually found a publisher with the aid of Norwegian sociologist Lars Mjøset, who immediately recognized its quality and wrote the book's fine introduction.

Crotty was not a professor but an intellectual rooted in practical experiences and strong but unconventional politics - Irish nationalism and Third World populism, tinged with admiration for the American populist, Henry George. Once in a blue moon, backgrounds like this enable someone to write a book which we professors, weighed down by disciplines and schools of thought, could never write. There are some token references to comparative historians and sociologists (including myself), but this book is an original.

This is an economic history of humankind from the beginning to the present. It covers only agriculture and animal husbandry, but has been the basic economy for most of history and remains so for most humans today. From it has come human biological sustenance and property relations. The first great originality of the book lies in its concern with human nutrition, how humans managed biological survival from plants and animals, and how they branched out into different modes of nutritional adaptation. The second great originality is to derive from this a theory of social development from the Neolithic age to the present. And the third great originality is the powerful culminating analysis of how Western individualistic capitalism "undeveloped" much of the Third World by destroying its nutritional basis. Given the power and originality of these arguments, I feel it is my primary duty to present them, rather than to engage in my own critique. This should convince you that this book is a must-read.

From the original hunter-gatherers ("living like animals") came pastoralists and agriculturists. Agriculture developed most in fertile river valleys, where all land was cultivated and surplus capital generated industry and services, thus creating "civilization". Since there was no extra land, individuals could not work to produce further marginal value. There was no private property and social relations were profoundly collectivist. Everyone was trapped into dependence on the community. In a separate line of development among pastoralists in Asia appeared a fateful Darwinian adaptation toward "lactose tolerance", enabling pastoralists to digest their animals' milk (most of the world's population are lactose intolerant and cannot do this without getting sick). Their ability to consume milk and milk products also gave them a surplus and capital. However, since good grazing land was scarce, the marginal productivity of labour was again zero and collectivism (based on clans) again dominated.

Crotty now embarks on his cattle-grazer's theory of history. The population surplus produced by these pastoralists, combined with the extensivity of grazing practices, led them into invasions/ migrations southwards and westwards. Crotty briefly explores their incursions into China and Africa (stand-off between lactose-tolerant cattle-grazers and agriculturalists), India (caste and holy cows), the Near East (the ultimate destruction of its civilizations), and the Mediterranean (private property in slaves, eventually a dead-end). Yet he focuses on their migrations into the Central European forest-lands. Here subsistence was tough, involving back-breaking forest-clearing to uncover fairly poor quality land. Yet land was plentiful and so the individual created marginal productivity and value, unlike anywhere else. Survival depended on a mixed pastoral/ agricultural economy generating surplus food and fodder for the animals to last over the harsh winters. So private property appeared in land and in capital, in the form of cattle, homes, crops and food. Crotty says capitalism had uniquely emerged in central Europe by about 2000 BC - a dating far earlier than anyone else's. Eventually savings and investment led to technological innovations in agriculture and warfare, developing European civilization.

After more conventional sections on the rise of Europe and its transport revolutions (navigation and railways/ steamships) enabling conquest of much of the world, Crotty turns more interestingly to the consequences. Where settler colonies wiped out the natives, they could introduce individualistic capitalism on terra nullis. It flourished there among colonists who were used to it back home. But elsewhere individualistic capitalism was imposed on large native populations in land-scarce environments, as for example in India, Indonesia and Africa. Their prior economic systems had resembled those of the world in earlier times: land was scarce but not labour, whose marginal productivity was therefore near-zero. Their varied but more collectivist property systems were now arbitrarily dismantled, and colonial elites and a few native clients appropriated all ownership rights. In post-colonial states the only difference has been to increase the number of native capitalists.

This imposition of an alien system of production "undeveloped" the Third World. Neither of Crotty's conditions for development are met -- that "more people are better off than in the past and that fewer people are as badly off as was the case hitherto". Western agricultural and veterinary science made improvements for the owners but not for the population as a whole. The Europeans did bring more public order, public health and medical science, but the subsequent improvements in health occurred without any improvement in nutritional standards. The human and the cattle population both increase while their consumption levels decline. They live, but undernourished. The cattle produce less milk and meat. Only unconquered countries like China and Japan escaped this degradation, and their successful development, whether capitalist or not, has been much more collectivist.

As Mjøset notes, this is a devastating attack, not on capitalism, but on the forced imposition of an individualist capitalism out of context, where labour was plentiful but land was scarce. It would not have developed autochthonously across the Third World and it brutally disrupted existing economies. The natives were forced out of adequate subsistence economies to become surplus landless labourers or peasants occupying marginal lands. Inequalities, especially in cattle-ownership, widened. Therefore Crotty advances twin proposals to restore development to the Third World: reduce population levels and restore the commons. Only this would undo the damage done to the world by Western colonialism. How frustrated he must have been as a development consultant, recommending such unfashionable policies!

All this was written before it became clear (in the last decade) that absolute living standards in the poorest third of the world's countries had turned downward, and before the AIDs pandemic began to decimate the populations of many of these countries. Most historical pandemics have struck populations with declining nutritional levels. Perhaps this one does too. Nowadays most radicals tend to attack neo-liberalism and the US for global undevelopment. Perhaps the real target is the entire Western economic system.

Finally, a few brief criticisms. Though Ireland is used frequently and fruitfully as the first European colony, Crotty's contemporary comments on Ireland sometimes err -- the "Celtic Tiger" remains livelier than he suggests, while Protestant hegemony in the North is substantially weakening. More importantly, Crotty did not live to see the sustained development now occurring in some post-colonialist regions like India and South-East Asia. These do tend to have more collectivist elements in their political economies. But they also have other non-economic benefits derived from their prior civilizations, like literacy, effective states, shared cultures and higher levels of social cohesion. Economic determinism like Crotty's has its limits and indeed I would make objections on this score to many of his historical arguments.

Nonetheless, Crotty uses his distinctive brand of biological/ economic materialism to very powerful effect. Here we have a treatment of "the European miracle" which is highly critical and not remotely Euro-centric. It is also highly plausible - though one would have to assemble bodies of experts with very diverse technical backgrounds to assess its ultimate truth-content. But all social scientists and historians with broad comparative interests, especially in the economy, demography and human health of the South of the world, should read this book and reflect long upon it. What a pity the author is no longer with us.

Michael Mann

Professor of Sociology, UCLA;

Visiting Professor, Queen's University Belfast, Ireland

Review by Professor John Hall, Department of Sociology, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, in American Historical Reviews, October 2004

Raymond D. Crotty. When Histories Collide: The Development and Impact of Individualistic Capitalism. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira. 2001. Pp. xxxvi, 311. Cloth $75.00, paper $29.95. http://tinyurl.com/399nxk9

This is a highly original and engaging book, somewhat mad but wholly convincing on vital issues of the age; it offers nothing less than a philosophic history of humanity. The author was an Irish farmer turned statistician, who then became an agricultural economist for international aid agencies before finishing his career as an economic historian in Dublin. Earlier works by Raymond D. Crotty offered striking theses about cattle and about Irish economic history, and these were flavored by an idiosyncratic mixture of loyalties-to Irish nationalism, the views of Henry George, and to Third World populism more generally. Crotty died in 1992, but the ambitious manuscript he left has now been put into excellent shape by his son, ably abetted by Lars Mjøset (who offers a fine introduction, helpfully distinguishing Crotty's views from those whom he might otherwise seem to resemble).

1. The baseline for the argument is a particular view of life within agrarian circumstances. The Neolithic Revolution is seen as having effectively caged human populations within fertile river valleys. There was no excess land, and so no sense of individual effort given that a production ceiling had been reached. Accordingly, social life was profoundly collectivist; private property scarcely existed, making just about everyone dependent on the larger community. This static equilibrium has characterized most of the historical record.

2. Change eventually came from the pastoralists of the roof of the world. Most human beings are lactose intolerant; that is, they become sick if they consume milk. Adaptation amongst pastoralists led to lactose tolerance, allowing the possibility of a surplus and personal capital. However, limits to grazing land meant that no general evolutionary step was taken. Crotty gives stimulating accounts of the inability of pastoralist invasions to produce fundamental change within most of the agrarian world. He describes both the stalemate between agriculturalists and pastoralists in Africa and China, and the destruction of Near East civilizations. Fuller accounts are offered of the uniqueness of the Hindu and Mediterranean worlds, both evolutionary dead ends due to their respective failures: sanctifying cows and depending upon slaves.

3. But an evolutionary break did occur at the margins. The forests of Central Europe were relatively unpopulated, thereby allowing individuals to generate surpluses through their individual effort. As early as 2000 B.C. a wholly new form of political economy had emerged, namely that of individualistic capitalism. The combination of agriculture and husbandry became ever more effective, allowing for an accumulating increase in capital and prosperity. Technological innovations, revolutions in transport, and conquests of foreign lands enabled Europe to dominate the world.

4. Crotty has a strikingly differentiated view of the impact of the West on the rest of the world. A first route was that of European settler societies. Here economic development did occur under the aegis of individualist capitalism-something made possible, he wryly notes, as a result of the destruction of native populations. A second route was at once more common and more disastrous. The application of individualist capitalism to collectivist societies leads, in Crotty's view, to nothing less than "undevelopment." Population can increase, and so, too, can the production of all sorts of commodities for export. But there is no fit between native institutions and capitalist individualism, and the result is all too often a combination of declining nutritional levels for the majority together with increasing advantage for the very few who effectively act as agents of the West. The third route stands in contrast to this. Some societies were never incorporated into European empires. The possession of their own institutions makes it possible for endogenous development to take place, in collectivist rather than in individualistic form. The classic case is Japan, but Crotty's general point-that institutional autonomy matters-has a great deal of force, and it applies more widely than is realized.

5. There are problems with Crotty's account. In the last chapters, Ireland is considered in detail as an exemplar of undevelopment. This makes little sense now, given the performance of the "Celtic Tiger" over the last fifteen years. At a more general level, there is an opportunity/cost to the account. If we benefit from the reduction of world history to a single set of variables, we lose from the refusal to take any other factor seriously. But the historical record has unquestionably been affected by world religions and by political forms. Still, no one should now write a world history without coming to terms with this fabulous book.

John A. Hall

Professor of Sociology, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

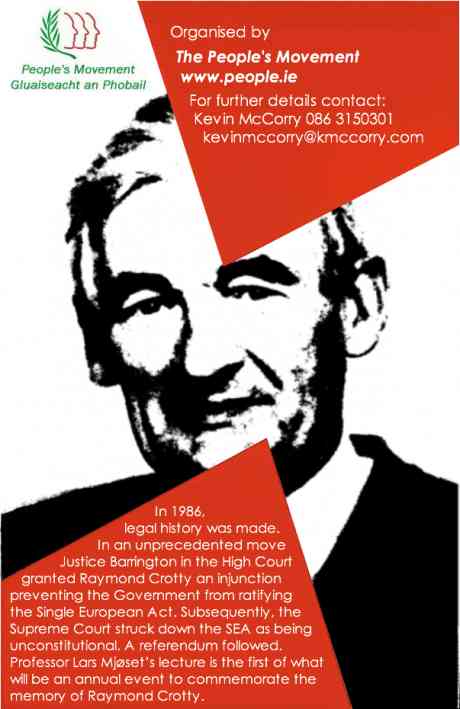

Farmer, economist, development theorist, historian, and political activist, Raymond Crotty (1925-94) was one of the most original thinkers to come out of modern Ireland.

|

national |

anti-capitalism |

press release

national |

anti-capitalism |

press release

Wednesday October 13, 2010 22:48

Wednesday October 13, 2010 22:48 by O. O'C. - People's Movement

by O. O'C. - People's Movement kevinmccorry at kmccorry dot com

kevinmccorry at kmccorry dot com 086 3150301

086 3150301

printable version

printable version

Digg this

Digg this del.icio.us

del.icio.us Furl

Furl Reddit

Reddit Technorati

Technorati Facebook

Facebook Gab

Gab Twitter

Twitter